Diagnostic Applications in Healthcare

Where people are first exposed to Bioelectromagnetics is often via their day to day experiences in their career or workplace. In many laboratory experiments for as long as a signal is great than zero, it is still acceptable to consider the signal detectable. These studies may involve recording or transdermal or insertion of electrodes to acquire biological signals such as electrocardiogram, electromyogram, or electroencephalogram to mention a few examples.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Related Techniques

MRI uses a strong static magnetic field plus time varying fields to influence how atomic nuclei behave inside the body. The scanner then detects faint radiofrequency signals emitted as those nuclei return toward their usual state, which can be reconstructed into images.

Several design choices keep this usable in clinical environments. The system shapes the fields in space and time, synchronizes signal collection, and compensates for motion. What matters for bioelectromagnetics is the coupling between fields, tissue, and conductive structures.

Recording Bioelectric Signals

Tests like ECG, EEG, and EMG measure voltage differences on the skin that arise from coordinated electrical activity in the heart, brain, and muscles. The body acts as a volume conductor, so electrode placement and skin contact affect what is captured.

Clinical systems filter noise and reduce interference from the environment. They also manage safety around patient connections, since sensors and cables can unintentionally couple to external fields. The end product is a time series that clinicians interpret in context.

Detecting Biomagnetic Signals

Electrical activity also produces magnetic fields, usually far weaker than what most environments generate. Biomagnetic measurements aim to detect those fields without direct skin contact, using highly sensitive sensors and shielding strategies.

In clinical and research settings, this approach can complement electrical recordings because magnetic fields are shaped differently by tissue conductivity. Bioelectromagnetics helps explain what is being measured and why the instrumentation is unusually demanding.

Electrical Property Measurements and Impedance

In clinical applications applied to the knowledge of the appropriate electrical properties of the human body, there are several methodologies used in this regard, one of which involves the use of high-frequency AC. It is possible to address this issue. Tissue impedance can be considered in the same directive as tissue resistance is addressed. As everyone knows, different tissues contain different level of charges, and have different resistance properties. Like for example, their impedaance pattern may change with respect to the different levels of hydration, breathing in and breathing out, or some changes in the components of the tissues occurring at a given point of time.

Electromagnetic Tracking for Image Guidance

In some procedures, clinicians track the position of a catheter or instrument using low power electromagnetic fields generated near the patient. A sensor in the tool detects the field and the system estimates location and orientation in real time.

This is a practical example of induction and field mapping in a busy clinical space. Conductive materials, nearby equipment, and patient anatomy can distort the field, so calibration and workflow discipline matter.

Therapeutic Uses of Electromagnetic Fields

Therapeutic applications use fields to stimulate, heat, cut, or otherwise interact with tissue in controlled ways. These tools are usually tightly parameterized, meaning frequency, intensity, pulse shape, and duration are specified in protocols. The goal here is to explain how they work in principle, not to judge outcomes.

Neuromodulation and Stimulation Approaches

Some therapies apply time varying magnetic fields or electrical currents to influence nerve activity. The basic mechanism is that changing fields can induce currents in conductive tissue, which can affect how neurons fire.

In clinics, this can look like external stimulation devices or implanted systems that deliver programmed pulses. Even when two devices target similar anatomy, the field geometry and dose settings can differ, which is why clinical protocols are usually quite specific.

Electrosurgery and Energy Based Ablation

Electrosurgical tools deliver radiofrequency energy through an electrode to cut tissue or control bleeding. Heating occurs because current passes through tissue and energy is dissipated, with local effects depending on contact, waveform, and time.

Ablation systems use related principles to create a targeted zone of tissue change. From a bioelectromagnetics view, the key issues are current density, thermal spread, and how nearby conductive structures shape the field in unintended ways.

Therapeutic Heating and Clinical Hyperthermia

Some clinical systems intentionally heat tissue using electromagnetic energy, often at radiofrequency or microwave ranges. Energy absorption depends on tissue electrical properties, geometry, and perfusion, which can carry heat away.

Because heating can extend beyond the intended region, treatment planning tends to rely on modeling, temperature monitoring, and conservative margins. The mechanism links field distribution to power deposition, then to heat transfer in living tissue.

Pulsed Fields and Field Assisted Interventions

Pulsed electromagnetic or electrical field systems deliver short bursts rather than continuous energy. Depending on settings, pulses can emphasize stimulation effects, transient membrane changes, or localized heating without long dwell times.

One area under study uses strong, brief electric fields to alter cell membranes in a controlled way, sometimes paired with drug delivery concepts. In clinical use, this is framed through device indications and defined parameters, since small changes in dose can change what dominates.

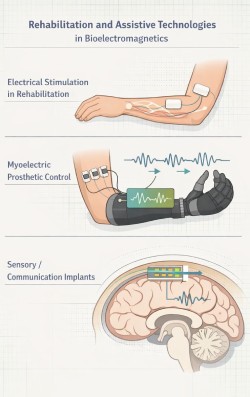

Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies

Rehab settings bring bioelectromagnetics down to the scale of repeated sessions and daily use devices. Here the focus is often on how devices interact with nerves, muscles, and sensors over time. Practical constraints matter a lot, including skin tolerance, comfort, and compatibility with other equipment.

Electrical Stimulation in Rehabilitation Practice

Some rehab devices apply electrical pulses through surface electrodes to activate muscles or influence sensory nerves. The mechanism is direct depolarization of nerve fibers, with pulse width and amplitude shaping which fibers respond.

Clinical use is usually structured around placement, timing, and monitoring for skin irritation or discomfort. Because the same stimulation can feel different across people and days, protocols often include adjustment rules to keep exposure within intended bounds.

Myoelectric Interfaces and Prosthetic Control

Myoelectric prostheses use electrodes to detect muscle activation signals in the residual limb. Those signals are small and noisy, so systems rely on amplification, filtering, and pattern recognition to translate them into control commands.

This is bioelectromagnetics in a sensing role rather than a stimulation role. The interface has to manage sweat, shifting contact, and interference from nearby electronics, since signal quality directly affects how reliably the device can interpret intent.

Sensory and Communication Implants

Some assistive technologies use implanted electrodes to deliver patterned stimulation to nerves involved in hearing or other sensory pathways. They typically include an external component that captures sound or other inputs and an internal component that converts it into electrical pulses.

The key mechanisms involve coupling through tissue, electrode design, and safe charge delivery. Long term clinical management focuses on programming, monitoring, and ensuring the implant interacts predictably with other medical procedures that involve strong fields.

Clinical Monitoring and Device Based Applications

Monitoring and implanted devices are where electromagnetic interactions can be both helpful and tricky. Many systems depend on sensing tiny signals while operating in environments full of other electronics. The practical question is often how to preserve signal integrity and avoid unintended interference.

Implanted Cardiac Devices and Leads

Devices that monitor and influence heart rhythm use electrodes to sense intracardiac activity and deliver paced pulses when programmed conditions are met. Leads act as conductors inside the body, so their placement and design influence both sensing and stimulation.

External fields can sometimes couple into leads, and medical procedures that use strong electromagnetic energy may require special precautions. Device teams often document exposure considerations as part of routine clinical management.

Wearables, Patches, and Remote Monitoring

Wearable monitors measure electrical signals, motion, and sometimes bioimpedance, then transmit data wirelessly. The electromagnetic piece includes both the sensing front end and the communication link, each with its own noise and safety considerations.

In clinical workflows, remote monitoring raises practical questions about data quality, missing signals, and artifact detection. The mechanisms are not mysterious, but they are sensitive to real life conditions like movement, skin contact, and other nearby devices.

Electromagnetic Compatibility in Care Environments

Hospitals are dense with emitters, from wireless networks to electrosurgical units, plus many sensitive receivers. Electromagnetic compatibility work aims to make sure devices keep functioning as intended when they share space and power.

This includes shielding, filtering, grounding strategies, and testing under expected interference conditions. Clinically, it shows up as equipment placement rules, cable management habits, and specific cautions for patients who have implants.

Emerging and Experimental Research Areas

Clinical bioelectromagnetics keeps evolving because sensors get more sensitive and devices get more targeted. Some ideas aim to bring advanced imaging closer to the bedside. Others focus on linking stimulation, sensing, and computation into closed loop systems that respond to physiology in real time.

Portable and Low Field Imaging Concepts

Research groups are exploring imaging systems that use weaker magnetic fields and different signal strategies than conventional MRI. Lower field strengths can change signal behavior, which affects how images are formed and what kinds of artifacts dominate.

Magnetic Guidance and Particle Based Approaches

Some experimental approaches use magnetic fields to influence the motion of particles or to concentrate energy in a localized region. The underlying physics is straightforward, but the biological environment adds complexity through blood flow, tissue barriers, and immune responses.

Where These Technologies Appear in a Hospital

Bioelectromagnetics is not confined to a single department. It shows up wherever measurements, imaging, stimulation, or energy delivery are part of routine care, often in spaces designed around shielding, workflow control, and specialized staffing.

- Radiology suites with MRI and related systems

- Operating rooms using electrosurgical energy devices

- Cardiology services managing implanted rhythm hardware

- Neurophysiology labs running EEG and EMG testing

- Intensive care units relying on dense monitoring networks

- Rehabilitation gyms using stimulation and sensor based tools

- Outpatient clinics using portable diagnostics and wearables

- Research units piloting emerging field based technologies

Signals, Fields, and Care: A Practical Wrap Up

In medical electromagnetics, instead of several distinct devices, it is more accurate to associate it with a language shared by physics, physiology, and clinical work. When one seeks an understanding of technologies in terms of mechanisms and limitations, one can succeed in grasping the essence without relying on advertising and shaming.

Indeed, any field does not have uniform effects on the human body. For instance, fields are known to generate currents, displace electrically charged particles, generate heat unlike any other energy form, work with sensors and wires given the necessary frequency and configuration dependence.

Quick Links

⚠️ WATCH CAREFULLY! THIS IS WHAT YOUR PHONE DOES TO YOU EVERY DAY!

— VAL THOR (@CMDRVALTHOR) November 21, 2025

How many of you carry your phone in your pocket?

How many sleep with it next to your head?

If you knew what your body is absorbing…

you’d think twice.

In the video, the EMF meter explodes into RED the second… pic.twitter.com/B3BlT0oKg7