EMFs in Occupational Settings

Workplaces can create EMF patterns that differ from home or public spaces because equipment runs at higher power, operates for longer periods, or brings workers closer to active sources. In bioelectromagnetics, occupational exposure is usually described in terms of tasks, locations, and equipment states rather than job titles alone. The same site can shift from low background levels to pronounced field zones depending on what is switched on and where people stand.

Industry, Utilities, and Heavy Equipment

In factories, especially, there are a lot of elements with electricity: huge engines, generators, the elements of a distribution system and high voltage cables, etc. All these elements form low-frequency electromagnetic fields and low-frequency electric fields when a load current flows in the cables busbars or energized panes. Also, installation jobs may take into account position and use of various other parts internally and externally to the substation.

Typically additional illustrations at a specific point are task-directed. The health effects of a task done while standing next to a transformer at the digging machine, for example, will differ from those related to operational duties in the control room. Many works tend to count normal conditions as a fraction different from incidental tasks such as testing, repairing, turning off, or re-tying work, since the person is exposed to many items.

Healthcare and Clinical Technologies

Hospitals and clinics include equipment that intentionally generates electromagnetic energy for imaging, monitoring, or device function. Some sources are steady and predictable during operation, while others appear in pulses or bursts as part of normal use. This leads researchers to describe exposure in terms of modality, duty cycle, and the distance between staff and equipment during procedures.

The same room can also contain many overlapping sources. Patient monitors, power supplies, and communication systems contribute to a layered environment where background fields sit alongside more localized fields near specific devices. In bioelectromagnetics research, careful mapping helps separate what is coming from a primary device versus what reflects the general electrical environment of the facility.

Transportation, Mobility, and Field Variability

Transportation workplaces add motion and changing geometry. Rail systems, aviation environments, shipping, and roadway infrastructure can all involve power electronics, traction systems, radar or communication equipment, and dense wiring harnesses. The EMF environment can shift as vehicles accelerate, brake, or change operating mode, which means exposures may be intermittent rather than continuous.

Because workers often move through many micro-environments, personal monitoring is frequently used to capture time-series data. Instead of treating the job as one uniform condition, studies may look at segments such as time spent in a cab, time near traction equipment, time on platforms, or time performing inspections near energized components.

EMFs in Urban and Built Environments

Cities concentrate electrical infrastructure, so everyday EMF conditions tend to be shaped by distribution networks, building wiring, and communication systems operating in parallel. Unlike many workplaces, the urban environment is shared and mixed-use, with exposure patterns that change block by block and floor by floor. Bioelectromagnetics research often treats the built environment as a patchwork of sources that differ in frequency, strength, and spatial reach.

Power Delivery and Distribution Networks

Transmission networks, distribution networks, and switchyards are major components of the electrical supply system in urban settings. Mostly, a variety of studies are classified depending on the size of the City, and are concerned with tap-off sites, cables, bus bars, transformers, circuits, the generation, control and distribution of the electrical energy; the voltages and the frequencies of the components such as generators and motors. These AC systems are very dynamic in that they adapt to the consumers’ load and therefore much of the dominate electric and magnetic fields that can be measured at a distance of a few meters from the generator rotate with the systems in place.

The structure of these systems can be seen as relatively complex and non-uniform and the necessity to build quite large nc-compact sources of electric and magnetic field in a certain shape and time distribution requires the study of the sources of ultralow-frequency electric and magnetic field intensities.

Buildings, Wiring, and Indoor Electrical Loads

Inside buildings, EMFs come from wiring routes, electrical panels, and the devices connected to them. Sources can be localized, like a power supply near a desk, or distributed, like circuits that run through walls and ceilings. Indoor environments also vary with occupancy and usage, since loads change when heating, cooling, lighting, and appliances cycle on and off.

This is why indoor exposure studies often include room-by-room surveys. They may distinguish between background levels in a space and near-field conditions close to particular devices. The language of “presence” is important here because a device can be present in a room without contributing much unless it is operating, loaded, or in close proximity.

Wireless Communications and Layered Frequency Bands

Urban areas host many radiofrequency sources, including broadcast transmitters, base stations, and local wireless systems. These sources operate across different bands and with different patterns, from relatively steady transmissions to traffic-dependent signals that fluctuate with use. Environmental measurements often focus on ambient field strength over time and across locations rather than on any single device.

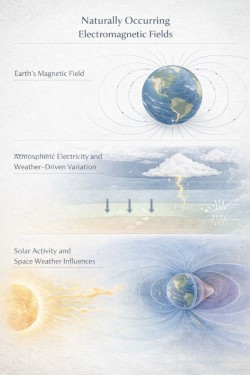

Naturally Occurring Electromagnetic Fields

Before considering man-made sources, bioelectromagnetics also accounts for the Earth’s own electromagnetic environment. Natural fields tend to be broad in scale, shaped by geophysics and atmospheric processes rather than by a single identifiable device. They differ from many technological sources in stability, frequency content, and how they vary with weather and solar activity.

The Earth’s Magnetic Field as a Baseline

The planet’s static magnetic field provides a continuous background that living systems have always experienced. It changes with location, altitude, and geology, and it can show smaller variations over time. In exposure discussions, this field often serves as a reference point because it is persistent and global rather than tied to a local installation.

Atmospheric Electricity, Lightning, and Weather-Driven Variation

The atmosphere carries electrical structure, including fair-weather electric fields and rapid transients during storms. Lightning produces intense electromagnetic pulses across a broad range of frequencies, though the duration is brief. These events illustrate how natural EMFs can be highly dynamic, with sharp peaks that are not well represented by long-term averages.

Solar Activity and Space Weather Influences

Solar emissions interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and upper atmosphere, producing disturbances that can change geomagnetic conditions. These effects can be subtle in daily life yet measurable with appropriate instruments. They also vary with latitude and with the timing and intensity of solar events.

How Exposure Is Measured and Categorized

Exposure is usually treated as a set of measurable variables rather than a single number. Researchers define it by the kind of field present, the strength at relevant locations, and the timing of contact with those conditions. Categorization helps compare studies across workplaces, cities, and outdoor settings even when sources differ.

Researchers also use consistent descriptors to keep comparisons meaningful, since “exposure” can refer to a brief close-range task, a full work shift, or background conditions over weeks. These descriptors do not interpret what the measurements mean for people; they describe what the instruments captured in a particular setting.

Common exposure descriptors include the following

- Frequency range of the field

- Electric field strength and magnetic field strength

- Duration, intermittency, and duty cycle

- Distance to the source and spatial gradients

- Whole-body versus localized exposure zones

- Environmental background versus near-field conditions

The choice of descriptors depends on the research question and on the environment being studied. A survey of urban background radiofrequency conditions uses a different approach than a task analysis near industrial conductors. In both cases, the goal is to translate a complex field environment into a description that can be measured, repeated, and compared.

Frequency as the Main Organizing Framework

Frequency is a practical way to group EMFs because it often tracks the kinds of sources involved. Static fields include the Earth’s magnetic field and some specialized technologies. Low-frequency fields commonly reflect power systems, while radiofrequency fields reflect wireless communications and some industrial processes.

Field Strength, Spatial Patterns, and Measurement Units

Field strength captures how intense a field is at a location. Electric fields are often described in volts per meter, magnetic fields in tesla (or related units), and radiofrequency exposures may be described through power density or related quantities depending on the context. These quantities refer to different physical aspects, so they are not interchangeable.

Time, Duration, and Intermittency

Exposure can be continuous, cyclical, or event-based. Some sources run steadily, like energized infrastructure, while others turn on and off as part of normal operation. Work tasks often produce short intervals of higher exposure separated by longer periods of lower background.

Proximity, Near-Field Effects, and Coupling

Distance is one of the clearest drivers of exposure because many sources produce stronger fields close to the device or conductor. Close-range conditions are sometimes described as near-field, where electric and magnetic components may behave differently than they do farther away. This matters for measurement because probe placement and orientation can influence what is recorded.

How Scientists Study Exposure Across Environments

Environmental and occupational EMF research relies on approaches that match real-world complexity. Instead of assuming a single stable source, studies often treat exposures as mixtures that change with location, activity, and time. The goal is usually to characterize patterns reliably enough that different settings and populations can be compared.

Area Monitoring and Environmental Mapping

Area monitoring uses fixed instruments or repeated measurements at defined locations. This approach is common for describing built environments, such as residential areas near infrastructure, public transit spaces, or indoor zones with identifiable electrical sources. Mapping helps show spatial gradients and identifies where conditions differ across relatively short distances.

Personal Monitoring and Time-Activity Profiles

Personal monitoring captures what an individual experiences as they move through settings. Devices may record field levels continuously, producing time series data that can be matched to diaries, shift schedules, or task logs. This allows exposures to be described as sequences, such as “commute,” “workstation,” “equipment bay,” and “break area.”

Source Characterization and Equipment-State Tracking

Some studies focus on identifying contributions from particular sources. This can involve measuring fields at different distances from a device, comparing operating modes, or recording how readings change with load. For example, a system’s field signature may differ between idle, ramp-up, and full operation, even if the equipment stays in the same place.

The Map, Not the Verdict

Environmental and occupational exposure to EMFs is best understood as a description problem first. Workplaces, cities, and natural systems each create distinct patterns that vary in frequency, intensity, space, and time. Bioelectromagnetics approaches these patterns by measuring them carefully and by using categories that make different settings comparable.

Quick Links

⚠️ WATCH CAREFULLY! THIS IS WHAT YOUR PHONE DOES TO YOU EVERY DAY!

— VAL THOR (@CMDRVALTHOR) November 21, 2025

How many of you carry your phone in your pocket?

How many sleep with it next to your head?

If you knew what your body is absorbing…

you’d think twice.

In the video, the EMF meter explodes into RED the second… pic.twitter.com/B3BlT0oKg7